Making A Scene: Jefferson Place

September 2017 marks the 60th anniversary of the opening of The Jefferson Place Gallery: a small, cooperative gallery dedicated principally to showing the work of DC-area contemporary artists of the late 1950s.

Founded by five American University professors and Alice Denney, the gallery quickly evolved from being an extension of the AU faculty’s pedagogy to becoming an early supporter of the Washington Color School. It would go on to host exhibitions featuring prominent national and international contemporary art figures including Jack Tworkov, Robert Goodnough, Toko Shinoda, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns.

The exhibition featured paintings and sculptures by the 11 founding gallery members: George Bayliss, Lothar Brabanski, William Calfee, Robert Gates, Colin Greenly, Leonard Maurer, Helene McKinsey Herzbrun, Kenneth Noland, Mary Orwen, Shelby Shackelford, and Joe Summerford–as well as other artists featured on The Jefferson Place Gallery’s walls Robert d’Arista, Elmer Bischoff, Gene Davis, Tom Downing, Max Elias, Robert Goodnough, Patrick Heron, Jacob Kainen, Fred Maroon, Howard Mehring, Claire Falkenstein, David Park, Hilda Shapiro Thorpe, Frederic Thursz, and Jack Tworkov.

Below is the catalogue essay prepared by the curator for the exhibition.

Making the Scene: The Jefferson Place Gallery and Washington, DC

by John Anderson

John F. Kennedy once jokingly summarized 1950s Washington, DC, as “Southern efficiency mixed with Northern charm.” Contemporary visual arts were barely represented in the city’s cultural mix, despite its being the country’s capital. In 1956, the National Gallery of Art housed painting and sculpture by dead artists only. The American Art Museum—then called the National Collection of Fine Arts—was limited to a narrow hallway in the Museum of Natural History. An Institute for Contemporary Arts started in the 1940s by poet Robert Richman presented occasional, primarily educational programs and exhibitions of non-local artists at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Although it employed local artists as guards, The Phillips Collection mostly devoted its walls to displays of art from the permanent collection, while the Pan American Union mounted shows by artists from member countries. Joseph Hirshhorn was a decade away from giving his collection of modern and contemporary art to the Smithsonian Institution; the museum that bears his name wouldn’t open until 1974.

Courtesy American University [ #15 ]

The catalyst for a professional gallery focused on Washington artists was at first glance an unlikely candidate. Alice Denney had moved to Washington in 1950 with her husband George, a lawyer on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee under Fulbright. Although interested in the arts from childhood, she was at that time more an appreciative audience than impresario. In fact, before arriving in DC, trained nutritionist Denney’s only real job had been consulting the wives of longshoremen around Boston about the nutritional value of their meals. [1]

Still, as a student and young wife, Denney had been increasingly drawn to the visual arts. While helping to support her husband, who was completing his JD at Harvard Law, she studied drawing and painting at night at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. After Harvard, the couple moved to New York, where George worked toward a Master’s in Soviet law at Columbia. The birth of their first child paused Denney’s formal art training, but her interest continued. Once a week, she would venture into the city to visit a friend. The two would gallery-hop, explore museums, and from time to time check out the scene at the Cedar Bar, already famous as an artists’ hangout, just to watch the giants of Abstract Expressionism like de Kooning and Kline verbally (and on occasion, physically) duke it out.

Private Collection [ #16 ]

By spring 1957, he decided that, although not without talent, she did not have what it took to excel as an artist, and encouraged her to put down the paintbrush. Dazed, Denney responded, “what should I do?” Mulling over the course of several months, she was suddenly inspired: she would start an art gallery with her AU artist friends. Denney, Orwen, McKinsey, and by this time, Summerford, were joined by Robert Gates, AU art department chair and highly respected mainstay of the still minimal DC art scene. With the return, a few months later, of sculptor Bill Calfee from an early, and unsatisfying, retirement to Vermont, the gang became six strong.

A Place, A Plan

On a summer afternoon as she and Orwen drove along Connecticut Avenue NW, Denney spotted the sign for an office rental at the corner where 18th Street, Connecticut Avenue, and block-long Jefferson Place met. The second-story walk-up above a rug store sported several rooms with walls big enough to accommodate large paintings. One huge glass window overlooked Connecticut, one of the city’s major thoroughfares; the other faced Jefferson Place. Putting down $250, Denney secured the location, officially 1216 Connecticut Avenue, from landlord Alex Dematatis in early August 1957. It would be another month before the six founding members would decide to name the space after the quiet side street: The Jefferson Place Gallery.

As the month of August progressed, the group debated what kind of space Jefferson Place would be. They finally settled on a cooperative structure, with artists paying a monthly fee of $15 towards gallery overhead. Artists would also be responsible for the printing and mailing of announcements, as well as refreshments at the reception. Thirty-three percent of sales went to the gallery. Denney, who was to be the full-time director, agreed not to take a salary until the gallery became self-sustaining — which it never did.

Courtesy William H. Calfee Foundation [ #128 ]

As a sign that the sleepy Washington art scene was changing, Jefferson Place turned out to be just one of three new galleries that debuted that season. The others were Gres Gallery—opened by Tatyana Gres, substantially funded, and featuring a prominent stable of rising international stars, including Fernando Botero, Marisol, Antonio Taipes, Yayoi Kusama, and Grace Knowlton– and the Art Rental Gallery, whose purpose was self-evident. But from the start, Jefferson Place positioned itself as uniquely responding to artists’ vision and needs. The gallery’s first exhibition, a group show simply titled “First Group Show,” attracted media attention both before and after the opening. The Washington Star’s articles remarked on the novelty of the city’s first cooperative gallery, and the strong AU ties of most of the participants. The show also was previewed in The Washington Daily News, which quoted an anonymous member as saying this would be “the first serious collective statement of contemporary art in Washington.”1

The October 10, 1957, opening featured the five founding partner artists—Orwen, Summerford, Calfee, McKinsey, and Gates—as well as some from the “wish list” artists: George Bayliss, Lothar Brabanski, Leonard Maurer, Kenneth Noland and Shelby Shackelford, whose last name was misspelled on the invitation. Also included was Colin Greenly, a last minute recommendation who had recently exhibited in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art.

The invitation itself carried a mini-manifesto: “The Jefferson Place Gallery will exhibit painting and sculpture in the contemporary idiom. The single standard used in the choice of these artists has been their common attitude toward creative expression rather than pursuit of a particular style or fashion. Individually, their work differs widely within the common search for new and significant form. As a group they offer to Washington an important collective statement.”

The Press Gang

The gallery’s ability to attract media interest—both general and art critical—continued throughout the 1957-1958 season. A Post article about the opening lauded “the event of the past week.”[2] Reviews of the first show’s actual contents praised most of the artists for their use of color, most notably McKinsey, Bayliss, Noland, and Shackelford. Generally good notices were given to subsequent solo shows of work by Calfee, Bayliss, and Noland.

Courtesy Hilda Shapiro Thorpe Estate. Image: Isaac Wasuck [ #163 ]

Looking back at the end of the exhibition year, the Post critic, Leslie Judd Portner (later Ahlander) determined that “the success of the gallery… is a tribute to the improved state of art in Washington, and to the willingness of the public here to accept the more advanced forms of contemporary painting.”[4] Denney continued to explore ways to attract media attention that were not necessarily tied to an exhibition. A March 15, 1960, profile in the Post on Harvey Moore, who owned a bronze foundry on M Street in Georgetown, dovetailed with work he cast for William Calfee’s solo exhibition at the gallery that month. In the run-up to the 1959 season opener, “Approaches to Contemporary Painting,” the Star promoted “informal lectures and seminars” with gallery artists, in which “Alice Denny” [sic] was described as griping about gallery visitors who could claim to have made the paintings with their eyes closed: “Sometimes… I think I’ll put up a blank canvas and tell the next person who says that to go ahead and try.”[5]

Other coverage involved more orchestration: in January 1958, Denney coordinated with a furniture store, Modern Design, to display several large paintings by Kenneth Noland. The article by Thomas Wolfe, soon to be known as New Journalism superstar Tom Wolfe, framed the juxtaposition as a means to prove that contemporary art can be lived with: the painting can match the couch.

Of course, activities of gallery artists didn’t always parlay into promotion for the gallery. New York exhibitions featuring Calfee, McKinsey, or Noland might be mentioned in the Post, but without reference to the Jefferson Place Gallery. Even reviews of local activities by gallery artists—at the Corcoran, Watkins Gallery, or elsewhere—were prone to ignore their connection to the gallery.

A Space Becomes a Scene

While reviews were certainly plentiful, it wasn’t the only media coverage Jefferson Place capitalized on. Shortly after the gallery opened, Denney was selected as one of three jurors— along with Alonzo Aden of Barnett-Aden and Katheryn Eichholz of the Obelisk Gallery—to judge The Washington Post’s Christmas Painting Project. Ads promoting the event featured pictures of the jurors and their affiliations, giving the new Jefferson Place enormous play. The lesson was simple: anything out-of-the-ordinary that the Jefferson Place Gallery, or its members, could do was an opportunity to promote the gallery.

Denney’s genius for understanding that to succeed in Washington, even a gallery needed social cachet, was already apparent. She made the most of connections to create a scene in which artists rubbed shoulders with patrons, political movers and shakers, and people interested in the arts whom she found interesting. Jefferson Place quickly became an almost daily hangout for influential figures like Abe Fortes—who was influential to establish the Hirshhorn Museum—and US Representatives John Brademas and Sid Yates, men who within the next decade would champion the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Courtesy Becky Gilliam [ #189 ]

In setting a schedule and actually running Jefferson Place that first year, Denney and her able assistant Freda Mulcahey drew on the expertise of Calfee, Gates, McKinsey, and Summerford, all of whom had managed AU’s Watkins gallery. Exhibitions lasting roughly three weeks came down on a Saturday; new ones were installed on Sunday with the help of Denney’s husband, George, the exhibiting artist, and Summerford. The crew would occasionally break to gawk from the second-floor picture window as President Eisenhower made his way to church.

Six days a week, the gallery was open. The lunch hour tended to be busy, with nearby foot-traffic wafting in to discuss the work. Sales sometimes proved difficult with wishy-washy connoisseurs: house wives needing permission of husbands, or husbands needing approval of wives. It got to the point where Denney detested trying to sell the work. For some exhibitions, the only work that sold was the work she bought. McKinsey handled the books, issuing reports and tracking income. Denney recalls paying her not in dollars but with a Jasper Johns print, Coat Hanger. During its first months, to everyone’s surprise, the gallery did manage to eke out a profit.

Outside Influences

Getting Jefferson Place artists into museum and gallery shows in New York and other established art scenes was another Denney goal. During numerous trips to New York, she would call on dealers with growing reputations for innovation, such as Leo Castelli, Andre Emmerich, Betty Parsons, Martha Jackson, Elinor Poindexter, and Stable Gallery’s Eleanor Ward to help nurture relationships she or her artists had previously established. When Jefferson Place artists had exhibitions in New York, Denney often transported the work, aided by her husband or Orwen.

Courtesy American University [ #198 ]

Denney’s enthusiasm for new art was not always appreciated by her gallery artists. On one visit to New York she purchased a small Robert Rauschenberg combine called “Cage” out of Leo Castelli’s bathtub. Although it was for her personal collection, she put it temporarily on display in the gallery, provoking Summerford to ask why in the world she would buy such an atrocity. Orwen, on the other hand, loved it.

Including artists from outside the membership in official shows was something baked into the cake of the Jefferson Place from its founding documents. (Although Jefferson Place was a coop, Denney had the liberty to bring in other artists. The other five principals could in theory veto an artist she brought in, but they never did.)

This openness to cross-pollination was already manifest during the second half of the gallery’s inaugural season. Solo-exhibitions in winter and spring featured an artist from out of town, even out of the country—Toko Shinoda.

Shinoda already had been featured in a number of gallery and museum shows, including the Museum of Modern Art. Her strong calligraphic brushwork caught the attention of Robert Gates, who suggested Denney organize an exhibition of her work. In the process of making arrangements with Bertha Schaefer Gallery, Denney thought it only courteous to contact the Japanese embassy in Washington and invite them to the opening. In response, the embassy suggested hosting a demonstration of Shinoda’s working process—a happy suggestion, as it turned out. While the February 1958 exhibition received the usual mentions in calendars and gallery notes, the demonstration received wide coverage. As much a society event as it was an art event, descriptions of her process in the Washington Evening Star and Washington Post—minimal brush strokes, use of a seal, destroying rejected pieces—were coupled with a list of who’s-who in attendance, as well as compliments on her kimono.

Import-Export

Shortly after Jefferson Place opened, a tall man from Kentucky, with an armload of paintings and a thick French accent, had walked into the gallery. His name was Frederic Thursz. On break from the University of Kentucky, where he was a professor of art, Thursz was in town to visit family for the holiday. Denney was interested in his paintings: a mix of monochromes with thick surfaces. (She would eventually give him a show.) Evidently, Thursz also liked what he saw, and offered an exhibition to the artists of the Jefferson Place at the University of Kentucky.

12 Washington Artists (from the Jefferson Place Gallery) opened in fall 1958 in the University of Kentucky art gallery. It snagged a handful of articles and blurbs in the student paper, The Kentucky Kernel, and a positive review in the Lexington Sunday Herald-Leader by critic Clifford Amyx, who called it “indicative of some significant things in contemporary art.”[6] Jefferson Place’s first foray beyond its home base was a success.

Denney’s ability to make the most of serendipitous connections and unlikely resources in her determination to discover and promote artists and the Jefferson Place gallery was highlighted again in spring 1959, when she found herself hosting a dinner for painter Peter Lanyon, then considered one of the most important artists to emerge in post-War Britain but largely unknown in America. The event celebrated the opening of 11 British Artists, work by the St Ives Group of Cornish-based artists that unexpectedly had been brought to the gallery by Barbara Burton. Burton, a painter and former AU art department secretary who had spent a year studying art in Cornwall with Lanyon and others, had put the show together; Jefferson Place gave it a home.

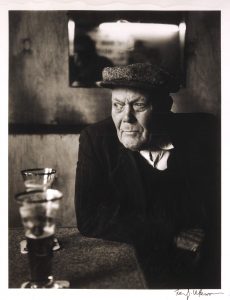

Jack’s Back, Bob’s Not—and Pittsburgh Discovers DC

Within a month of 11 British Artists closing, the gallery opened an exhibition of drawings by Jack Tworkov. Tworkov, an important figure in the New York School, had been a regular presence at American University, going back to 1947, when Calfee—then chair of the art department—invited him to teach for part of a summer. Professional and personal relationships between Tworkov and the art department continued for over a decade.

Courtesy American University [ #18 ]

In Tworkov’s case, Denney’s perseverance paid off. But other attempts to bring key New York artists to town were not successful. Since her purchase of the Rauschenberg combine, Denney had become close friends with Castelli. Their correspondence even pointed to a possible exchange between the galleries. Denney also wanted to give Rauschenberg a solo-exhibition. But Castelli also indicated the busy schedule of his artist made this impossible, though he did it with greater grace than Ward had. (As consolation, Rauschenberg would eventually be included in a group exhibition.)

On the other hand, Denney’s queries to Gordon Washburn, head of the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, brought opportunity. In early 1958, Denney contacted him in an effort to have him visit Washington to consider Jefferson Place artists for the prestigious biennial. Learning she was too late for that year, she tried again in the fall of 1960, at a time when Washburn was planning his travel itinerary. As a result, he came to town and works by Calfee, Howard Mehring, and Noland were included. It had been decades since a Washington artist made it into the biennial exhibition—let alone four (José Bermúdez from Gres Gallery was also chosen).

Courtesy American University [ # 12 ]

Maroon’s photography studio on the floor above the Jefferson Place Gallery enabled him to pop in regularly, chat up Denney, and, in good humor, razz her about the artwork. Eventually he suggested the exhibition, and Denney agreed on the condition he manage the show and the gallery, which would otherwise be closed for the summer. Maroon included Yoichi Okamoto—who later became White House photographer under LBJ—and Robert Phillips. The show drew favorable notices. But more telling was the attention it received from Steichen, acclaimed photographer and then director of photography for the Museum of Modern Art, who took half an hour away from a busy schedule to see the work in the gallery. He later advised Maroon to “keep the show going as long as the people come.”[7] They extended the exhibition by another week.

New Directions

Whatever else the Jefferson Place was doing, it was having an impact. By the fall of 1959, a new cooperative gallery, The Origo, opened in DC. Spearheaded by Tom Downing and Howard Mehring, it was quickly compared to Jefferson Place. However, before its second anniversary, it was shuttered by the city for code violations. Capitalizing on this misfortune, Denney brought Mehring and Downing into the Jefferson Place group, eventually giving Mehring and Downing solo-exhibitions in November 1960 and April 1961, respectively.

In summer 1960, a Denney family cross-country car trip visting friends, and frequently camping on the roof of the station wagon, was the impetus for an ambitious exhibition. In major cities—Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco—Denney put on a suit, left the family in a hotel, and visited local galleries. It was an opportunity to introduce herself, introduce her gallery, and curate an exhibition for the Jefferson Place: Art from America’s Cities.

With earlier exhibitions by Shinodo, Tworkov, Thursz, and the group from St. Ives, the Jefferson Place had established similarities between the working styles of gallery artists to other artists in the world. Denney’s intention was to compare the Jefferson Place gang to some of the most important contemporary artists, like Elmer Bischoff, Claire Falkenstein, Robert Goodnough, David Park, Robert Rauschenberg and Peter Voulkas. As the exhibition’s press release would state, the show was assembled “…to convince people in Washington that the work of the artists in DC was just as good as the art in New York, LA, San Francisco, and Chicago.”

Although the Washington Star’s critic found the show title pretentious, Leslie Judd Ahlander of The Washington Post picked up on Denney’s concept: “Although they are exhibiting alongside painters with established reputations…[they] are equal to, and in some cases better than, those of the West Coast and New York.”[8]

Art in America’s Cities was intended to be the start of a new direction for the gallery. As McKinsey noted to Jack Tworkov, “Things go well at the Jefferson Place Gallery too. Alice has taken over completely (it’s no longer a cooperative) and opened with a swell show.…”[9] After Howard Mehring’s exhibition of all-over paintings in mid-October, Denney followed up with work by New York artist Robert Goodnough, whom she had met in the 1940s at the Cedar Bar.

Goodnough had been impressed with the turnout at his exhibition, considering no one in town knew him. But Denney, ever resourceful, had some tricks up her sleeve. She contacted her landlord—Alex Demitatis—who was a member of the AHEPA society: a Greek organization in the District of Columbia. He showed up with a band of Greeks, en masse. For her part, Denney provided the event with the best watered-down cheap sherry one could funnel into more expensive bottles. It was a frugality that Demitatis—notorious for penny pinching—would have

appreciated.

Courtesy Robbin Mullin [ #202 ]

As 1961 began, the artists from the Jefferson Place were once again involved in a group show outside of Washington: this time at the 20th Century Gallery in Williamsburg, Virginia (now the Williamsburg Contemporary Arts Center). Richard Oils, art critic for the Virginia Gazette, found the works of Colin Greenly, McKinsey, and Hilda Shapiro notable, and gushed over the works of Thursz and Mehring (although he also likened Mehring’s work to a 19th century dress pattern). Back in DC, Denney was also anxiously awaiting a visit from Gordon Washburn, who was traveling the country to curate for the latest Carnegie International.

Meanwhile, in the gallery, it was business as usual. Davis showed some of his first thin stripe paintings, and Downing offered paintings of large dots. The Star’s critic likened the former to mattress ticks and awnings, and the latter to linoleum floor coverings.[11] Shapiro had her first solo show with the gallery, as did Baltimore artist Liz Whitney Quisgard. Quisgard’s enormous paintings were too big to be transported to DC in her car, let alone heaved up the stairs and into the door of the gallery. She ended up re-stretching the 7 x 15 foot canvases on the floor of the gallery.[12]

The Seeds of a New Museum

In late November 1960, Alice attended a cocktail party hosted by Julian and Elisabeth Eisenstein. Eisenstein, a frequent visitor to the gallery, already owned works by artists in the Jefferson Place stable. Mrs. Eisenstein’s sister and brother-in-law, an artist, were in town for Thanksgiving, and the Eisenstein’s thought it appropriate to introduce him to members of the DC arts community. As Eisenstein recalled, Alice said, “Don’t you think we should have a museum of contemporary art in Washington?” to which he replied, “yes! Let’s start one.”[13] With the expanded focus of Jefferson Place’s recent exhibitions with artists from outside DC, plus the series of lectures within the gallery, a museum certainly made sense. At the very least, it had the potential to receive more funding than the Jefferson Place’s current structure could support. The museum would also benefit from the support of Alice’s many art-world and political connections, which continued to expand.

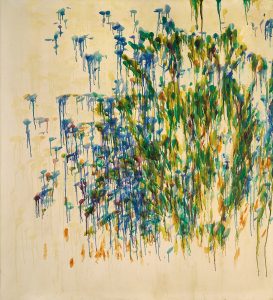

© Estate of Jack Tworkov / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. [ #192 ]

Money remained an issue. “I may show at Jefferson Place this spring,” McKinsey conveyed to Tworkov. “Alice needs some local shows. Importing them, even from NYC, has proved expensive.”[15] The financial strain was also reflected in a letter Denney wrote to Castelli. “I would like to have a show of your gallery group here but unfortunately our funds for outside shows are limited.” Deterred by fiscal limitations, but unfazed, she left the door open to “explore the possibilities later.”[16]

The idea of a contemporary museum took hold and grew. By 1961, concrete plans for the now named Washington Gallery of Modern Art were underway. A small board of trustees was assembled; among other things, they suggested Denney become the gallery’s director. She demurred, citing a lack of credentials, and instead recommended rising New York curator Henry Geldzhaller. The committee interviewed him but thought he “wasn’t right for Washington.”

The search for a director recommenced, and this time Denney was willing to be recruited. With many of her interests and energies getting pulled toward the museum, she thought it prudent for a second search committee to form: one that would find her successor at the Jefferson Place. The principle members of the gallery would eventually choose Nesta Dorrance to succeed Denney as director: a title she would hold until the gallery closed 13 years later.

As the gallery closed for the summer of ’61, Denney wrote a letter to Castelli, letting him know of her departure. With lose ends tied up, her tenure in the Jefferson Place Gallery—her first gallery project—came to an end. As summer turned to fall, a new chapter began in Denney’s career as a small but significant figure in the national arts scene of the 1960s. It would also open a new chapter in the history of the Jefferson Place.

Another Beginning

Dorrance, the Welsh-born wife of an economist at the IMF, was, as Denney had been, a housewife who appreciated art, studied painting, and even had won a few minor exhibition awards. As she opened the 1961-62 season, she maintained the same rigorous schedule that preceded her. Dorrance even followed up with Leo Castelli about exhibiting his artists at the Jefferson Place, eventually meeting with him in September.[17] As a result, the 1961-62 season of the Jefferson Place Gallery opened with a faint echo of the 60-61 season, with Jefferson Place Gallery artists exhibiting alongside several artists from Castelli Gallery.

Apart from Salvatore Scarpitta, whose assemblages of wrapped stretcher bars drew notice, the Castelli artists netted little press attention. Grabbing more ink were newcomers to the gallery. Robert d’Arista had just joined the painting faculty at American University. And Maxim Elias— who also exhibited as Max Elias, and Max K., to distinguish his exhibitions from his father’s exhibitions (also named Maxim Elias)—was a student of William Calfee’s and exhibited amusing assemblages and found objects. But these arrivals were outnumbered by departures: Downing, who joined the gallery the previous fall, had already moved on, as had seasoned gallery artists Bayliss, Noland, Shackelford, Maurer, and Brabanski.

Courtesy Michael L. Brabanski [ #197 ]

As 1962 progressed, the schedule got back on track with solo exhibitions. The Star would whine about the quality of Thursz’s paintings, and of the smaller scale of Robert d’Arista’s work. More favorable reviews were written for Gates’ watercolors of abstracted landscapes of river, sea, and sky, and for Eugene Langford’s “junk sculpture” of found scrap metal. Calfee received added attention for his dual exhibition with the Corcoran—he exhibited the finished pieces at the Corcoran, and the process pieces at the Jefferson Place: another pedagogical moment for the gallery.

The summer months were typically dull in DC. Galleries were closed; people left town to escape the heat and humidity. With the dearth of activity, the Post’s Ahlander took the summer of 1962 to interview several artists. They included Gates, Davis, Kainen, Summerford, Mehring, Downing, Calfee, and José Bermúdez. Seven of the eight were affiliated with the gallery, six actively. The contents of the interviews were transformed into the season’s opening poster for the fall of 1962, with the full contents of each interview reprinted on both sides, and promoting newcomers to the line-up: Luciano Pena-y-Lillo, Edward Kelley, Marilee Shapiro, and Peter Thomas. The poster also included an image from the Jefferson Place’s first opening, the caption erroneously dating it “1956.”

Between the opening of the Franz Kline memorial retrospective at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, and the arrival of the Mona Lisa at the National Gallery of Art, there remained a little room in the arts columns of the fall of 1962 to remark on the solo-exhibitions of Mehring and Davis—his last with the gallery until 1967, when he would show his micro paintings.

With the arrival of 1963, Jefferson Place would maintain a steady course with its nucleus from American University, and push evocative new forms from E.R. (ViVi) Rankine, Ed Kelley, Colin Greenly, Paul Reed, and Jennie Lea Knight. By January 1965, it also had relocated to 2144 P Street, where it renewed its place in the DC art scene, beginning with shows by newcomers Sam Gilliam and Willem deLooper. Eventually Jefferson Place’s new site would contribute to the opening of additional galleries along that stretch of P Street, well into the 1970s.

A Legacy

For a gallery that few expected to survive beyond its first couple years, what the Jefferson Place Gallery accomplished was remarkable by any standard. It endured and overcame the occasional stinging criticism from local press and the initial indifference of a public unused to contemporary art. It outlived several galleries that emerged to challenge it, and served as a model for some of the survivors. Through its continued support of local artists, and its diligent efforts to align the works by area artists to contemporary trends across the country, it attracted a following that in the end united to create and support a Washington museum of contemporary art. Major collectors like Melzac, David Kreeger, and Phillips purchased work from the gallery—purchases that would eventually be absorbed into museums in Washington and across the country.

Started as a lark by artist friends and a director who had never run a gallery, Jefferson Place Gallery succeeded in its most difficult task. It made a scene, and in the process helped to transform the cultural landscape of the capital.

Footnotes

1 “Art Show Won’t Be Dealers’ Choice,” Staff, c. October 1–5, 1957 The Washington Daily News

2 “D.C. Gets a New Kind of Gallery,” Leslie Judd Portner, October 13, 1957 The Washington Post and Times Herald

3 “Contreras’ First,” Florence Berryman, December 1, 1957, The Sunday Star

4 “Fine First Season,” Leslie Judd Portner, May 25, 1958 The Washington Post and Times Herald

5 “Viewers Invited To Question Artist,” Amelia Young, September 20, 1959, The Sunday Star

6 “Art Exhibit Opens Today At University,” Clifford Amyx, October 19, 1958, The Sunday Herald-Leader

7 “Steichen Photographs One Tree for Four Years,” Jean White, July 19, 1959, The Washington Post

8 “Strong Start At Jefferson Place,” Leslie Judd Ahlander, Sept. 25, 1960, The Washington Post

9 Letter from Helene McKinsey to Jack Tworkov, OCT. 14, 1960, Folder 17, Box 2. Jack Tworkov papers, circa 1926-1993. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

10 Interview with Alice Denney, dates variable

11 “Many New Shows Fill Local Art Galleries,” Florence Berryman, Jan. 22, 1961, F-7 The Washington Evening Star

12 Interview with Liz Whitney Quisgard, Jan 9, 2017

13 Interview with Julian and Elizabeth Eisenstein, January 2013

14 Letter from Helene McKinsey to Jack Tworkov, Feb 5, 1961, Folder 18, Box 2. Jack Tworkov papers, circa 1926-1993. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

15 Letter from Helene McKinsey to Jack Tworkov, Dec. 1, 1960, Folder 18, Box 2. Jack Tworkov papers, circa 1926-1993. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

16 Letter from Alice Denney to Leo Castelli, Dec. 6, 1960. Folder 26. Box 12. Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

17 Letter from Nesta Dorrance to Leo Castelli, 1961. Folder 26. Box 12. Leo Castelli Gallery records, circa 1880-2000, bulk 1957-1999. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.