Mary Pinchot Meyer

Mary Pinchot Meyer’s (October 14, 1920 – October 12, 1964) exhibition at Jefferson Place in November 1963, was given a rave review by Leslie Judd Ahlander in The Washington Post. Ahlander wrote “Using the tondo, or circular, canvas, Mary Meyer divides the area into curved and sinuous areas that sometimes seem to set the tondo to revolving as the colors succeed each other’s pull outward. Color, obtained through the use of plastic paint on unsized canvas, as is usual with this group of artists, is luminous and carefully thought out.”[1]

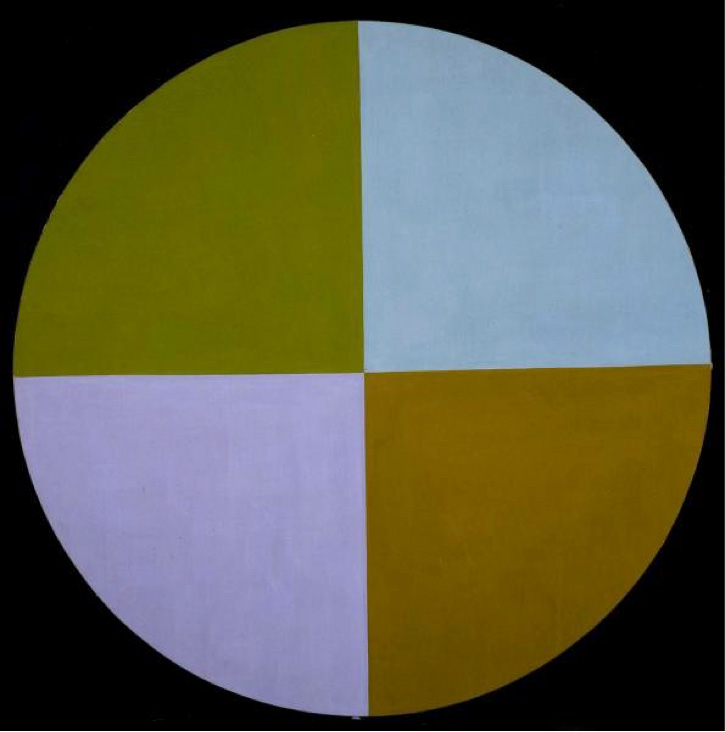

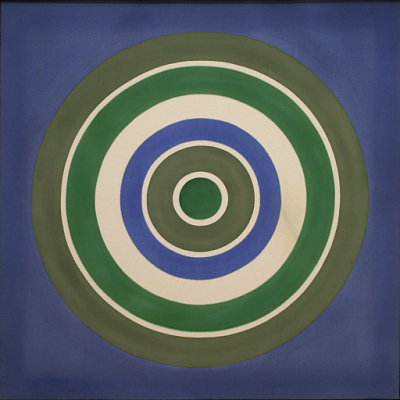

Ahlander situates Meyer’s work squarely within her contemporaries when she mentions “this group of artists.” The hard-edge geometric abstraction, as seen in Half-Light (to the left), is stylistically similar to other Washington artists. By employing a shaped canvas she worked in the inverse of artists like Kenneth Noland who, during the late 1950s and early 60s, painted concentric circles on rectangular canvases. Noland would eventually work with shaped canvases later in his career. Meyer’s use of what she called “the tondo,” curved circular canvas, and the straight hard-edge line of the colored quadrants, harmonize to create a symmetrically balanced composition. In Half-Light, the green and brown colors are contra pointed by the closely hued blue and purple. Meyer maintains symmetricity in her work, an aspect of practice that her fellow artists took seriously as well.

In 1964, Meyer was included in a traveling exhibition, Nine Contemporary Painters organized by the Pan American Union. The exhibition opened in Buenos Aires then went on to Rio de Janeiro. Fellow artists included in the exhibition, alongside Meyer, were Gene Davis, Tom Downing, and Sam Gilliam. This exhibition was packaged to show South Americans contemporary art by young or little known artists who had yet to achieve widespread success despite the quality of their work.[2] The curator of the exhibition, Lawrence Alloway, characterized the type of painting coming from Washington as unlike that being produced in other American cities: “In Washington a constant of several painters has been the use of flat color on unprimed canvas… the repetition of a single image is typical of this kind of painting, in which color, its tensions and its variable, is central.”[3] Alloway went on to describe Meyer’s work specifically, writing, “The paint in the tondos… of spectrally related colors, defining curved forms that roll in from the outer edge of the canvas… Meyer’s home is in a central area or point.”[4]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s there were several galleries in the area exhibiting related work — including the Franz Bader Gallery, Barnett-Aden Gallery and the Washington Gallery of Modern Art — but it was the Jefferson Place Gallery where Meyer found opportunity. She came to know the director, Alice Denney, as well as other artists who exhibited there, including Kenneth Noland, Ben Summerford, Robert Gates, and Mary Orwen. Meyer would, for a short time in 1960 or 1961, share a studio with Orwen and close friend Anne Truitt.

Lotus by Kenneth Noland, 1962. Used by permission of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, all rights reserved.

Meyer’s large scale, colorful abstract paintings exhibited at Jefferson Place Gallery fit within the modus operandi of the group associated with the Washington Color School. Her highly abstract compositions with flat applications of vibrant color that emit an energy and radiate off the canvas compare to Noland’s concentric circle paintings from this time, Morris Louis’s Unfurled canvases, and Paul Reed’s circles surrounded by fields of color. While at the time of her murder Meyer’s work was not commonly included in exhibitions with other artists, her paintings are easily connected to the work of her contemporaries.

Meyer was an artist who took her work seriously, and she was part of a tight-knit artistic community. She was an experimental artist who used various materials such as linen and acrylic in her practice. More scholarship on her paintings could determine her role as an influential member of a radical group.

Author Mollie Berger has worked in the Prints and Drawings department at the National Gallery since 2014. Her recent projects at the Gallery include co-curating a small exhibition of prints by Edvard Munch, teaching a seminar on Washington Color School artists, and giving pop-up gallery talks at the Gallery’s after-hours events. She graduated from George Washington University with a Master of Arts in Art History in 2014, during which time she held internships in the Prints and Drawings departments of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery of Art. While completing her Bachelor of Arts in Art History at the University of Vermont, Mollie worked in the curatorial office of the Fleming Art Museum. She also held positions at the Shelburne Museum in Shelburne, Vermont, and the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. An adapted version of her graduate qualifying paper on Kenneth Noland’s circle paintings and the psychoanalytic therapy of Dr. Wilhelm Reich was recently published for Refiguring American Art, a research project organized by Tate, London. Mollie’s research interests includes artists who have lived and worked in Washington, DC, early twentieth century American landscape painting, and the cultural impact of the Cold War.

[1] Leslie Judd Ahlander, “The Jefferson Place Gallery,” The Washington Post, Times Herald, November 24, 1963, G10.

[2] José Gómez Sicre, Nine Contemporary Painters: USA (Pan American Union, Washington, 1964), n.p.

[3] Lawrence Alloway, “Notes on the Painters,” in Nine Contemporary Painters: USA (Pan American Union, Washington, 1964), n.p.

[4] Ibid, n.p.